Unlike our archaic adolescent years of having to wait on a modem to dial-up for Internet (if we even had it at all), today’s teens have been raised on wifi and all the instant gratification it brings.

The problem with this is that reliance on “right now” and dissatisfaction with the present doesn’t stop at the Internet. It carries over into every aspect of their lives and comes with a slew added emotional baggage.

“Why didn’t she text me back yet? She doesn’t like me anymore!”

“He checked my InstaStory DM but didn’t reply.”

Sound familiar? Parents of tweens and teens often shrug off such anxious and gloomy thinking as normal irritability and moodiness — because, in large part, it is. Still, the beginning of a new school year, with all of the required adjustments, is a good time to consider just how closely the habit of negative, exaggerated “self-talk” can affect academic and social success, self-esteem and happiness. And, with the rise in popularity of shows like Netflix’s Selena Gomez produced 13 Reasons Why it’s important to pay close attention to your teens’ mood and be communicative as they ebb and flow through the challenges associated with growing up.

Psychological research shows that what we think can have a powerful influence on how we feel emotionally and physically, and on how we behave. Research also shows that our harmful thinking patterns can be changed.

You may not be of much help when it comes to sharpening your teen’s calculus skills. But you can play a huge role in helping your children to develop a critical life skill: the ability to take notice of their thoughts, to step back and view the bigger picture, and to decide how to act based on that more realistic perspective.

Taking notice of an alarmist or pessimistic inner voice is a universal experience. It has survival value; it often protects people from danger. And it’s often true that a worrying thought can act as a motivating force – to study, for example.

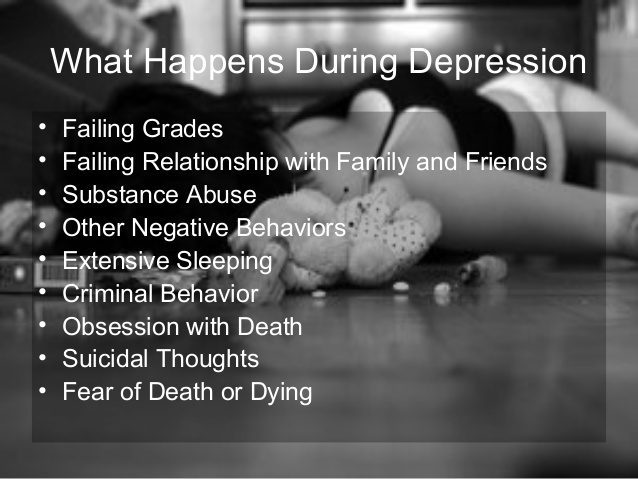

Still, the insecurities that adolescents feel as they undergo the multiple transitions necessary in growing up make them especially vulnerable to believing the worst. This tendency can lead to chronic anxiety, depression, and anger, and can interfere with relationships and success in school.

Teaching children about the importance of thinking more realistically may help protect them in the real world once they leave the comfort of your nest. According to a 2016 survey by the American College Health Association, 38% of undergraduates at 50 colleges and universities reported they had felt so depressed at some time during the previous year that it was tough to function. Some 60% had experienced an episode of debilitating anxiety.

The power of thoughts to impact feelings and behavior is a foundational principle of cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT teaches people how to recognize faulty negative self-talk, to notice how it makes them feel and act, and to challenge it. Parents can practice this skill themselves, and act as models as they guide their kids to question a thought by looking at the evidence for and against it.

If your child seems withdrawn, sad or angry, you may be able to identify a problematic thinking pattern by listening closely. Here are four key styles of negative self-talk to listen for:

Catastrophizing. One common thought habit is the tendency to jump to the worst-case scenario (“What if I fail the test and can’t play in the playoff football game?”). Scanning constantly for disaster ahead acts as a huge contributor to anxiety. And catastrophizing often leads teens to avoid people or become reluctant to try new things.

Focusing on the negative. Ruminating on a disappointment without taking into account the many positive and neutral aspects of one’s experience is often associated with sadness and depression. A missed field goal might overshadow everything else that happens one day – the good grade on a test, the lunch with friends, the new episode of their favorite show – and consume your high-schooler for days.

The “it’s not fair” complex. Interpreting every let down as a grave injustice – the “it’s not fair!” habit – often underlies teens’ anger and can harm friendships and family relationships.

The “I can’t” complex. Reacting habitually to difficult situations or to new opportunities with “I can’t,” rather than “I can try,” leads to helplessness. Changing the thought to “I can try!” encourages problem-solving and a willingness to be proactive, to take positive action — both keys to being successful and resilient.

For parents, the idea is not to dismiss the negative thought. Research has found that attempting to dismiss the thought can actually make it stick longer. Rather, challenge your child to face the thought, examine it thoroughly, and swap it with a more realistic and helpful perspective.

For example, if your child complains of not having any friends at their new school, pose questions that carefully and analytically examine the situation: “You had a group of friends at your old school and at camp – realistically, what are the chances you can’t make friends now? What actions can you take to reach out? What would you say to somebody else who worries about this?”

A helpful replacement thought might be: “It probably will take a few weeks to get to know people, but I’ve made friends before and there are things I can try. I can sign up for sports and after-school activities to meet people that way.”

More realistic and balanced thinking leads to positive action, which, in turn, tends to bolster confidence, enhance self-esteem and result in greater happiness.

If you found this article helpful, please share with friends and family by clicking the button below.