Dan Fabbio was a 25-year-old student working on his master’s degree in music education when suddenly, something changed. He became unable to hear music in stereo.

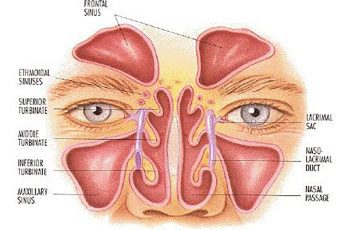

A short time later he was diagnosed with a benign brain tumor located in a part of the brain known to be active when people listen to and make music.

Fearful that he’d no longer be able to pursue his passions in music, Faccio sought out Dr. Web Pilcher, chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Rochester Medical Center, who along with his colleague, cognitive neuroscientist, Brad Mahon, had developed a brain mapping program.

Since 2011, they’ve used the program to treat all kinds of patients with brain tumors: mathematicians, lawyers, a bus driver, a furniture maker. Fabbio was their first musician.

The premise behind the program is to learn as much as possible about the patient’s life and the patient’s brain before surgery to minimize damage to it during the procedure.

“Removing a tumor from the brain can have significant consequences depending upon its location,” Pilcher says. “Both the tumor itself and the operation to remove it can damage tissue and disrupt communication between different parts of the brain.”

Prior to Fabbio’s surgery, the team spent six months studying the functional and structural organization of his brain, Mahon tells All Things Considered host Robert Siegel.

“We have a lot of experience mapping language in the left hemisphere,” Mahon says. “This was the first time we sought to map music … in the right hemisphere.”

Working with Elizabeth Marvin, a professor of music theory at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music, Mahon came up with a series of music tests for Fabbio.

They asked him to listen to piano melodies and hum them back while he underwent functional MRI scans. In between melodies, he listened to and repeated spoken sentences. The scans allowed the researchers to pinpoint the areas of Fabbio’s brain that are crucial for music and language processing. From those scans, they produced a three-dimensional map of Fabbio’s brain.

The map became a guide for Pilcher and his team during the surgery in July 2016. Fabbio was not only awake, but he once again performed the music and language tests, this time with his brain exposed. Marvin, who was in the operating room, scored those tests in real-time, helping the surgeons identify which areas to avoid.

Once the tumor was removed, Fabbio was given his saxophone and asked to perform a song he’d prepared for the moment. Out of concern that the deep breaths required for long notes could cause his brain to protrude from his skull, Fabbio and Marvin had chosen a Korean folk song and modified it so he could use shorter shallower breaths.

“He played it flawlessly, and when he finished, the entire operating room erupted in applause,” says Marvin. “It made you want to cry.”

Fabbio’s case is described in detail in a study published Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

If you found this story interesting, please share it with friends and family by clicking the button below!