Flooding means health issues that unfold for years.

While much of the country is still processing the unbelievable images of Houston completely submerged in water, public health officials are bracing for what will inevitably be a health catastrophe for years to come.

Though the loss of human life and health has been small relative to what the images suggest, the impact of hurricanes on health is not captured in the mortality and morbidity numbers in the days after the rain. This is typified by the apocalyptic problem of mold.

When a city is submerged a new ecosystem of fungal growth is introduced that will change the health of the population in ways that we’re just now beginning to understand. The same geography and infrastructure that have kept this water from dispersing created a uniquely prolonged period for the fungal overgrowth to fester, which can mean adverse health effects for years and even lifetimes.

The documented dangers of excessive mold exposure are many including respiratory symptoms, allergies, asthma, and immunological reactions. Guidelines issued by the World Health Organization cites a wide array of “inflammatory and toxic responses after exposure to microorganisms isolated from damp buildings, including their spores, metabolites, and components,” as well as evidence that mold exposure can increase risks of rare conditions like hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergic alveolitis, and chronic sinusitis.

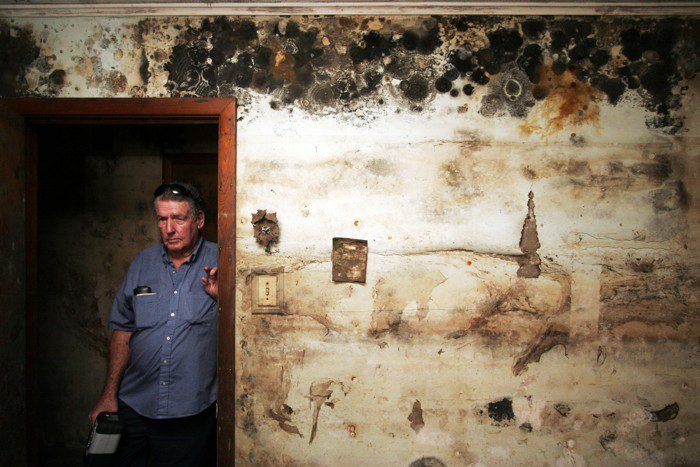

The best example of this in recent memory was twelve years ago in New Orleans. Katrina similarly, rendered most homes uninhabitable, created a breeding ground for mosquitoes and the diseases they carry and caused a shortage of potable water and food.

But long after these threats to human health were addressed, the mold exposure, particularly in low-income neighborhoods, continued.

Two years after Hurricane Katrina, a New Orleans resident poses in his mold-infested home. (Alex Brandon / AP)

The highly publicized “toxic mold” — varieties that send mycotoxins into the air and sicken anyone inhaling it cause the most concern right after a flood.

Researchers from the Natural Resources Defense Council held a press conference after Katrina about dangerously high levels of mold spores in the air. The group accused the Environmental Protection Agency of focusing only on exposures like arsenic, lead, asbestos, and pollutants such as those found in gasoline while ignoring mold exposure.

It should be noted that the EPA did respond at the time by issuing radio announcements and distributing brochures encouraging people to wear respirators when re-entering flooded buildings. These are prominently occupational exposures primarily affecting manual laborers.

While the more insidious and ubiquitous molds produce no acutely dangerous mycotoxins, they can still trigger inflammatory reactions, allergies, and asthma. The degree of impact from these varieties in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina is still being studied.

Molds also emit volatile chemicals that some experts believe could affect the human nervous system. Among them is Joan Bennett, a distinguished professor of plant biology and pathology at Rutgers University, who was living in New Orleans during the storm. She recalls that while some health experts were worried about heavy-metal poisoning or cholera, her primary concern was the fungus.

The devastation to the infrastructure in Houston is catastrophic and the scope of the long-term effects are beyond our current understanding. Short-term rescue funding is essential to saving lives, and supporting it is politically necessary. But most of the looming threats to human well being will outlast the immediate displays of concern. They will play out when the water and the cameras are gone, and when emergency funds allocated to Houston are exhausted. Mold will reveal the have and have-nots, marking the divide between people who can afford to escape it and those who have no choice but to “wait and see.”

If you found this article helpful, please share with friends and family by clicking the button below.